Normalising the Abnormal: Trinity College Dublin Decides what to do with its Collection of Stolen Skulls

Ciarán Walsh (curator.ie)

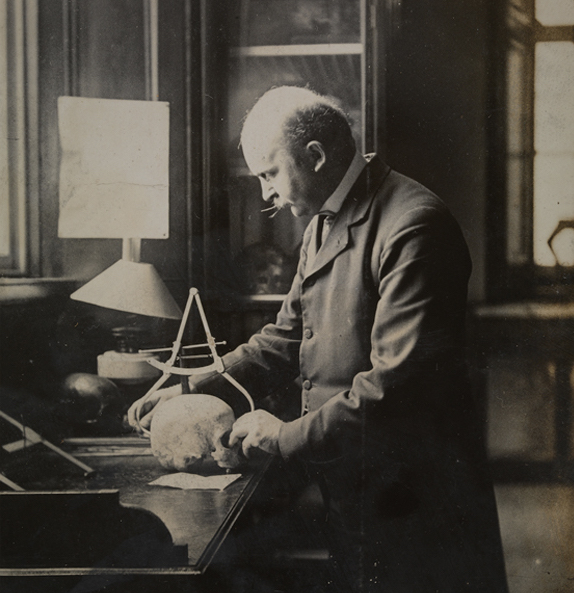

Charles R. Browne, the first graduate in academic anthropology at Trinity College Dublin (TCD), went to Inishbofin in 1893 with a plan to collect skulls in a burial ground Alfred Cort Haddon had robbed in 1890. The islanders remembered Haddon, and frustrated Browne’s endeavor (Browne 1993: 334). Marie Coyne, founder of Inishbofin Heritage Museum, began seeking the repatriation of the Haddon skulls in 2015, but made little progress until the Black Lives Matter movement forced TCD management to consider colonial legacies in 2020. Two years later, TCD sent a delegation from the newly established colonial legacies project back to Inishbofin to deal with the issue of the skulls.

Pegi Vail, who was co-editor of an introduction in AJEC‘s latest issue (Ferraz de Matos et al. 2022) on fairs and exhibitions where humans were displayed as exhibits, has covered the story of the skulls in the first post on AJEC’s blog on this theme, and I explore some of the underlying themes in this post. The repetition of ‘evidence-based process’ and ‘give us back our skulls’ in exchanges that followed the meeting in Inishbofin articulated a striking difference in perceptions of the problem, and I consider two aspects of this story. The first relates to the evidence-based strategy TCD adopted, the second to the historical context of the theft of the skulls, and the possibility that the strategy re-enacts colonial traditions associated with TCD. This argument pivots on the tactical use of an evidence-based process to dominate the process of deciding, and normalise the process of domination.

Evidence-based methodologies gained ground in medical science and health care in the 1980s and are modelled around the application of knowledge gained through systematic and synthetic research in an academic context to solutions that achieve consensus at a practical level. The Inishbofin case illustrates how these methodologies have spread into other areas, and Baba and Hakemzadeh (2012) provide a useful guide to literature in this field. This indicates that the social sphere constitutes a more challenging environment because public-interest and advocacy groups also produce knowledge, and two issues may arise in this context. The first relates to the standard, regulation and utility of evidence collected, and the second to the nature of the decision-making community.

With regard to evidence, the repatriation project met the colonial legacies team in September 2020, and both sides accepted evidence that the skulls from Inishbofin were part of the Haddon-Dixon collection, agreeing that the repatriation claim covered all twenty-four skulls in the collection. The colonial legacies team drew back from this position in October, insisting that evidence of the theft of the other skulls was not robust enough, and shaped their methodology accordingly (Hussain, O’Neill and Walsh 2022: 2). Perhaps the principle of replicating agreed modes of decision making will resolve this issue in time, but their handling of other evidence was equally problematic. The claim that Haddon was associated with TCD was incorrect, as was the claim that the theft of the skulls was part of a programme of Irish research conducted by Irish researchers. Furthermore, the colonial legacies team rejected evidence that the people of Inishbofin constituted an indigenous population at the time of the theft, and, in this context, argued that the repatriation by TCD of Māori remains in 2009 was outside ‘the limits of evidential review’ (ibid.).

I take the opposite view. The Anatomy Museum, TCD has a page on the Irish Museum Association website which states that the Māori repatriation was a ‘gesture [that] embodies the ethical paradigm shift in the approach to studying anatomy introduced in the 20th century’ (emphasis added). The committee managing the museum refused to repeat the ‘gesture’ in 2021, stating that regulation by the National Museum of Ireland and Medical Council prevented it from supporting a request for deaccession – a technical term used by museum mangers to describe the disposal of museum assets – lodged by ‘private individuals or historical interest groups’ (see my submission at TLCRWG public submissions).

Marie Coyne and I tested this evidence and confirmed that (a) the National Museum regulation is irrelevant because the collection predates the foundation of the independent Irish state, and (b) the collection does not come under the remit of the Medical Council. However, the Haddon-Dixon and Māori material were part of the Anthropological Collection in the Anatomy Museum and guidelines drawn up by the National Museum clearly place that collection under the jurisdiction of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of 2007, which establishes repatriation as a right. That puts the Anatomy Museum well behind the ‘ethical paradigm shift’ that has taken place in the twenty-first century.

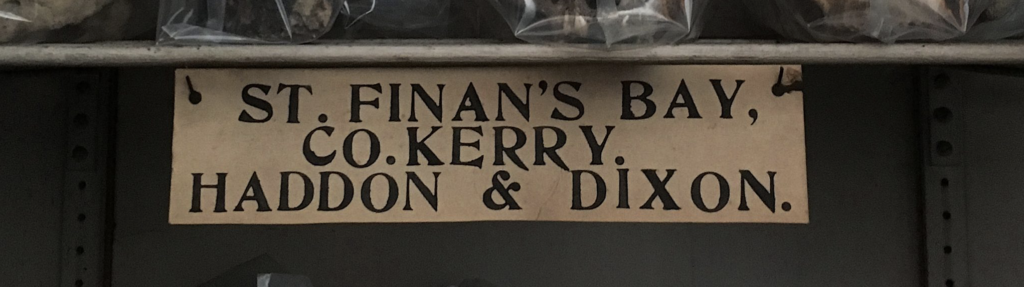

The colonial legacies team, as stated, ruled this evidence inadmissible on clearly arguable grounds, which suggests a tactical approach to evidence collection and management in light of the decision on Aran and St Finian’s Bay, and this brings me to the nature of decision-making communities. Baba and Hakemzadem’sreview (2012) identified transparency and consensus within communities as key elements of a viable evidence-based process, and the problem here is that the colonial legacies project does not see the communities of origin as part of the decision-making community, which it has defined as representatives of the academic community – including three trades union representatives – within the college plus three outsiders nominated by the Provost (see TLRWG terms of reference). To put this in perspective, a proposal made at the meeting in Inishbofin that the Provost nominate a suitably qualified and independent community representative was forwarded to the Provost and went unacknowledged at the cost of a consensus building measure.

Transparency is also a problem. For instance, the Senior Dean informed the Board of TCD in December 2022 that that the National Museum and Medical Council would be consulted in advance of any decision, even though Marie Coyne and I had already submitted documentary evidence from both, which, in the case of the National Museum, consisted of a formal statement by a government minister in response to an official question asked by a member of parliament. Furthermore, in advance of the minutes being published online, the community asked for a report on the outcome of the board meeting in terms of a roadmap. The colonial legacies team replied that the Senior Dean had sought clarification from all the statutory bodies and promised to share more information in February 2023. That is as opaque as it gets.

This is where colonial traditions come into play. I was struck by the historical symmetry of the colonial legacies team’s attempt to normalise as science an abnormal act of graverobbing in a series of lectures in Inishbofin, and Haddon’s transformation of his stolen skulls into anthropological specimens in a lecture in Dublin in 1892. More striking still was the increasingly fractious nature of exchanges as community members and associated researchers questioned aspects of the evidence presented and the procedures proposed by TCD.

That was not part of the script apparently, and it got me thinking about colonial traditions and institutional cultures. It seems to me that the tradition of reasoned criticism and cultural domination that is such a part of TCD’s colonial identity resonates with the exclusive claim to authority that is manifest in each utterance of ‘an evidence-based process’, especially in the linked contexts of colonial legacies and power relations between TCD and the communities it once subjected to craniological study.

TCD will decide what happens on 22 February 2023 and our best guess is that Marie Coyne will finally achieve the return for burial of the remains of the islanders’ ancestors. One thing is certain however: eleven crania from the Aran Islands and St Finian’s Bay will remain in the Anatomy Museum, despite verified and agreed evidence that they were part of the same graverobbing haul. How ‘normal’ is that?

About the author

Ciarán Walsh is a curator who, in 2012, began working with Marie Coyne on the repatriation of ancestral remains Haddon stole in 1890. Walsh graduated from the National College of Art in Dublin fadó fadó – a long time ago – and developed an interest in the historical divergence between contemporary visual arts practice and language-based folk culture. This led to an investigation of ethnographic representation, and, in 2009, he curated the internationally acclaimed exhibition John Millington Synge, Photographer in collaboration with scholars in TCD’s manuscript library. This was the beginning of a critical engagement with colonial legacies, and the same scholars facilitated equally groundbreaking work on the photographic archive of the Anthropological Laboratory TCD, which activated the repatriation project; Marie Coyne contacted Walsh in 2012 to enquire if she could show some of those photographs in the Inishbofin Heritage Museum, and Haddon’s photograph of the skulls he stole triggered a request for their return in 2015. Walsh completed his doctoral research in the Anatomy Museum in TCD in 2019, and successfully defended his investigation of the skull-measuring business in 2020. This laid the foundation for an independent postdoctoral monograph for Berghahn Books on Alfred Cort Haddon’s contribution to the modernisation of anthropology (in press), and a radical reassessment of his life and work for Bérose International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology. He is currently working on the connection between Haddon, Synge and the Aran Islands.

References

Browne C. R. (1893), The Ethnography of Inishbofin and Inishshark County Galway. Dublin: Printed at the University Press by Ponsonby and Weldrick. Reprinted from Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1889-1901), no. 3: 317–370, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20490464.pdf.

Baba, V. V. and F. Hakemzadeh (2012), ‘Toward a Theory of Evidence Based Decision Making’, Management Decision 50, no. 5: 832–867.

Ferraz de Matos, P., H. Birkalan-Gedik, A. Barrera-González, & P. Vail (2022), ‘Introduction: World Fairs, Exhibitions and Anthropology’, Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, no. 31(2): 1-14.

Hussain, M, C. O’Neill and P. Walsh (2022), ‘Working Paper on Human Remains from Inishbofin held in the Haddon-Dixon collection at TCD’, Trinity College Dublin, November, https://www.tcd.ie/seniordean/legacies/inishbofinTLRWGworkingaper.pdf.